White capitalism within communities of craftivism: mask making and health maintenance disparities during COVID-19

- 1Department of Communication Studies, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 2Department of Surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, TX, United States

When lockdown started, my anxiety kept me on a tight string—I (author 1) remember drowning in intense, omnipresent agitation as I used every “extra” moment I could to research mask styles, adapt patterns published online or distributed by different organizations to increase access to masks for better functionality, and distribute masks to those who needed them via an old ice cream bucket on my front bench. Yet, I recognized that the time I used, my ability to quarantine and so much more contributed to my privilege in doing so. I (author 2) had no masks on hand, so after watching a few tutorials online, I concocted my own makeshift mask. Not only did my MacGyvered creation not fit properly, it was superhot and lacked sufficient air flow due to the thickness of the fabric. Although this initial mask-making strategy wasn't very practical, I recognized the importance of having not only a mask but one that would fit such that it properly served its purpose: to preserve my health. By fashioning a collaborative, autoethnographic approach to understanding craftivism during the 2020 coronavirus crisis, from a Black scholar doing disparities and equity focused health communication work and a white scholar engaging activist rhetorics and digital media equity scholarship, our joint recognition of economic and infrastructural privilege offered understanding of how forms of pattern design (techne) and cultural community infrastructure influenced our maker agencies and constraints. Reflecting on our immersive mask-making experiences, we recognized a value of creating alternative economic structures, yet also unmasked significant racial agencies within craftivist communities which required cultural historic materiality and knowledge, time to create and revise, networked access, and physical risk. Here, we offer insight into how a crisis revealed systemic biases as agency to reorient ourselves toward anti-racist processes and practices.

1 Introduction

I (author 1) will never forget 16 March 2020—the day that the K-12 schools closed in Minnesota due to COVID-19. I remember watching the governor's streamed announcement over Facebook. Until that point, I had heard about masks from international students at the university in which I worked, but I had witnessed very few masked faces in public. I, like many people in the U.S., believed that COVID wouldn't reach us—that it wasn't global. Lockdown began as did a requirement to wear masks in Minnesota and then on Friday, 3 April 2020, the CDC posted the recommendation that people wear masks in public (Dwyer and Aubrey, 2020; Goldberg et al., 2020).

My older sister made my family our first masks, and I quickly realized that we would need more. I actually started feeling a sense of panic—how would we protect ourselves and our community members? I was privileged to have a sewing machine that my mother-in-law passed down to us when my partner and I started quilting in graduate school. As a child, my mom instructed me how to sew and I even had a class in middle school in which I made a pillow. When lockdown started, my anxiety kept me on a tight string—I remember drowning in intense, omnipresent agitation as I used every “extra” moment I could to research mask styles, adapt patterns published online or distributed by different organizations to increase access to masks for better functionality, and distribute masks to those who needed them via an old ice cream bucket on my front bench.

I (author 2) recall the start of the pandemic vividly. It was the second week of March at the beginning of my university's spring break. By this point, we had been hearing reports on the news about this new deadly virus that was rapidly spreading across the globe. I felt a bit sheltered from the impact because it was happening “over there” in countries that we'd seen or heard of having epidemics before. Never in my lifetime would I have imagined what we were about to endure. I initially faced the impending danger with a bit of arrogance which I later found to be complete ignorance. There were murmurings of a shutdown and, not realizing the severity of what we were about to face, I cheered when the announcement was made that we would not be returning to classes in person the following week. As an academic, the prospect of having a bit more time to relax and recover from a long semester was highly welcomed. As a naturally risk-averse person, I quickly became an early mask adopter; I began wearing a face covering before a state-wide mandate was put in place. I had no masks on hand, so after watching a few tutorials online, I concocted my own makeshift mask. As a Black woman with natural hair, scarves are abundant in my home so I used one that I'd previously used as a bedtime head wrap as the foundation for my face covering. It was polyester and it was thick! So while it wasn't ideal, the prospect of contracting COVID was even less so. I'd also heard that coffee filters would add an extra level of protection against airborne disease, so I added a few to the mix. There I was, venturing out to the market to get groceries in my homemade mask before masks were “a thing.” People stared, looking at me sideways in that “what the…” way. Not only did my MacGyvered creation not fit properly, it was superhot (did I mention it was made from polyester?) and lacked sufficient air flow due to the thickness of the fabric. With four coffee filters, it also was barely breathable. I recall one masked visit during which, covered in sweat and ready to pass out, I placed my groceries on the conveyor belt. I was grateful that I'd only selected a few items as I likely would have caused a scene due to a fainting spell if I'd purchased anything more. Although this initial mask-making strategy wasn't very practical and frankly should be classified as a failure, I recognized the importance of having not only a mask but one that would fit such that it properly served its purpose: to preserve my health.

Following efforts to respond to the coronavirus/SARS-2 pandemic, we attempted to figure out how to preserve public community health. Here, we share an autoethnographic account of our experiences to detail the intimate connection between crafting masks and community health. Noticing a difference in our ability to adequately respond (e.g., make shifting masks for ourselves and making masks for different communities) to a crisis of care, we critically contemplated what our cultural and public communities and institutions communicate by who has access to what health resources; specifically, whose health is privileged through a specific “ethic(s) of care” (Ahmed, 2004, p. 120; MacGill, 2019, p. 417)? Additionally, we found ourselves responding to the call made by Adams and Herrmann (2023) as they eloquently argued,

we need accounts of how racism is lived, how it happens in everyday contexts and how we are all relationally connected to those happenings, how it accumulates and accretes over time, what it means to carry the weight of racist pasts in the now, and how it feels to embody decades—centuries—of generational trauma. We need auto-ethnography to provide these first-hand experiences with racism, especially how it occurs in everyday settings and within and through institutions, including the academy.

Our concepts and emotional experiences of living through a pandemic offered historicity to how generations of racism, privilege, and oppression materialize at an exponential rate within a single, global health crisis.

Concerns exist when it comes to cultural differences in response to COVID-19 (Yap et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022; Lu, 2023; Rowland et al., 2023), the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color (Fortuna et al., 2020), and the labor of women of color during the pandemic (Elhinnawy, 2022; Blell et al., 2023; Flores Sanchez and Kai, 2023; Melaku and Beeman, 2023). In addition to institutional care, we noted how well-intentioned reorganization of labor in the form of alternative economic systems can also result in discriminatory impacts. For example, in response to the Trump administration's onset in 2017, the Women's March made pussy hats with the intention of standing for unity, yet critiques from non-binary, Black and Brown scholars and activists illustrated a discrepancy of impacts from the hat designs. Critiques surfaced from protesters about the name, gender centric, and racist privileging built into the construction of the hat (Malcolm et al., 2020, p 13). In more recent craftivist efforts of mask making, the Women's March organization solicited help through their #maskup response to educate their communities about the need for wearing masks, making masks for those in need of access to quality masks, and building public community through “stitch and bitch”1 sessions (Women's March, 2020). Yet both hats and masks can embody a “commodity activism,” where efforts of purchasing political statements can become a form of feigned agency performance by wearing feminist materials (Erdely, 2021). When privileging and exclusion continue through a narrow perspective conveyed within community chat or through purchases, “[a] do-gooding ethos often serves as a moral cover for harmful decisions” (Benjamin, 2019, p. 61) thus actively perpetuating systemic oppression through a guise of collaborative and collective political action (Repo, 2020). During a crisis such as COVID-19 when, what University Professor and the Wallis Annenberg Chair in Communication Technology and Society (Castells, 2012) recognized as, “alternative economic cultures2” are formed, how do ideologies influence the reorganization of how cultural care functions and who benefits from those reorganizations? During our mutual exigency to construct homemade masks in spring of 2020, we witnessed how craftivism, or the making and distribution of various masks and access to health maintenance, manifested through white capitalist privilege within networked communities, prompting ethical questions about how alternative economic cultures continue to buttress white privilege and supremacy.

Understanding how craftivism activates an ethic of care required an analytic approach capable of intimate understanding of sewing as a process (technê) and networked infrastructure of resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. As defined by professor of Literature at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, Chansky (2010), craftivism is the development of textile crafts such as “knitting, crocheting, sewing and quilting, latch or rug hooking, embroidery, and cross stitch” as a form of activism (p. 681). Credited with the first usage of the term “craftivism,” author Greer (2007) urged women to think about craft as more than women's work—instead to acknowledge craft as “something that has cultural, historical, and social value.” As a form of “everyday work,” craft can offer a means to stitch our communities together as the process of crafting and the crafts form new ways of joining together and preserving communities. In that “certain knowledges... may only be appreciated by taking part” (Price and Hawkins, 2018, p. 21), the hands-on knowledge production role of craftivist offered structural insight of cultural resources required for craft design. Yet, our academically refined analytic methods seemed maladaptive tools as we attempted to understand our experiences. When analyzing an alternative form of text, traditional methods do not adequately address nuances and, therefore, require critical analytic reflexivity (Enck-Wanzer, 2006, p. 193). Specifically, engaging in crafting masks offered critical insight into the technê of craftivism and shifted our analytic model from hegemonic, traditional forms of analysis. Additionally, by fashioning a collaborative, autoethnographic approach to understanding craftivism during the 2020 coronavirus/SARS-2 crisis, from a Black scholar doing health communication work focused on disparities and equity and a white scholar engaging activist rhetorics and digital media equity scholarship, provided joint recognition of economic and infrastructural privilege, space we needed to critically contemplate the experimentation that comes with makers' communities. Specifically, we could engage how forms (technê) of pattern design and cultural community infrastructure contextualized within our socially mediated communities influenced our maker agencies and constraints, privileges, and oppressions, of ourselves and people within our communities.

2 Dialogic autoethnographic method

Given our own early experiences with mask making and caretaking, autoethnography emerged as a means to understand structural knowledge of the systems that support the maker and making. As clarified by feminist writer and independent scholar Ahmed (2012), ethnographers offer perspective based within lived experience, requiring participation to compassionately understand as participant-observer (p. 1). Authoethonographers embody an immersive quality that requires accountability to multiple communities, local and academic. Understanding the mask-making alternative economic culture required not only that we make masks but also that we became a part of the mask-making communities in digital and local spaces while being critically reflexive about how those cultures privileged and constrained us and/or others. Not only is “thick description” as noted by ethnographer Clifford (1973) necessary, but it also offers insight into cultural, systemic privileging and racism as well as how we do our scholarship. Although this research began as a single pursuit by author 1, after the death of their sister during the pandemic, author 2 reached out by asking how they could support author 1. After hearing over and over how much author 1 talked about finishing this research, author 2 offered to co-author the piece. That “coalitional moment” (Chávez, 2013) changed how we both understood meaningful scholarship in that our joint vulnerability became an impetus for growth, and coalition became a means for survival, not only our personal survival but also our understanding of how generative scholarship grows by existing within and preserving a dialectic. Similar to Russworm and Blackmon (2020) collaborative article, we sought a meaningful dialectical understanding of the cultural zeitgeist that is mask making during COVID-19.

Prior to identifying individuals in this manuscript, we sought consent, following principles in line with the ICMJE recommendations. Documentation of consent was gathered using Frontier's consent form. Furthermore, we used minimal identifiers to protect the privacy of individuals we interacted with which resulted in examples used in this study.

Reflecting on our immersive mask-making experiences, we recognized a value of creating alternative economic structures, yet also unmasked significant racial discrepancies for craftivism by detailing how alternative economic agency required cultural historic materiality and knowledge, time to create and revise, networked access, and risk. Through our co-authored accounting, we embodied what Houdek and Ore (2021) noted as a politic that “will require a collective effort grounded in an embodied, situated, and relational praxis of co-conspiring—of breathing together in a desire to un-/remake the world” (p. 92) to offer insight into how a crisis revealed systemic biases as agency to reorient ourselves toward anti-racist processes and practices.

2.1 Craftivist agency as contained by white historic materiality and knowledge

Through everyday exigency, craft can become strings that hold communities together or/and even separate out different patterns or parts. Crafting is a response to something we face everyday, offering people a means to “mend it” or make life better. As noted by Leilliot,

Everyday life is what we are given every day (or what is willed to us), what presses us, even oppresses us, because there does exist an oppression of the present. Every morning, what we take up again, on awakening, is the weight of life, the difficulty of living, or of living in a certain condition, with a particular weakness or desire (Certeau et al., 2014, p. 3).

Crafting emerges from a specific context with specific needs in mind, in response to those specific needs. Further crafting forms a unique relationship between the maker and what is made—a value of process—that can only be engaged through direct experience in making because of the need for problem-solving during the process. In her book Things Worth Keeping, Christine Harold described that relationship as transformative in that

the unique aspects of a material object that can only be known through direct experience, is echoed again and again by those who craft. Craftspeople must know both their materials and tools intimately. Crafters must enlist their bodies and memories in the process. Good technique is developed over time, through patience and perseverance. Unsurprisingly, makers report that they themselves feel transformed though this transformation of matter into form (Harold, 2020, p. 185).

Through learning the process of craft, a maker and the made are weaved together as the body forms an object and builds muscle memory as well as techniques which influence a maker's identity.

The relationship between the crafter and craft can be understood by engaging historic fiber crafting which stems culturally from domestic beginnings. Craft theorist Auther (2010) identified, “given women's traditional domestic role, it is not surprising that the housewife is a key figure in critical considerations of fiber art, where she functions as a signifier for amateurism and lack of creativity” (p. 23). Yet, we see the potential for extending Auther's conception of a “housewife” as a key figure to fiber art to agency between compassionate community members. Author (1) felt a sense of “agency” to craft. While early conceptions of craft were situated in close relationship to the role of a housewife, now we see an extension of craft built through sisterhood, connection, and community. I (author 1) felt agency to craft masks in part because my sister and I talked about it. Agency is defined by Cooper (2011) as a disposition (p. 432). Responding to the pandemic by mask making was not felt by my spouse, who also knew how to sew, nor by some of my friends without sewing machines or knowledge. Part of agency is knowledge, making craft a knowledge base which is specific to a group of people; children may learn to sew from their caregivers (typically mothers or even grandmothers). For example, my (author 1) oldest child (age 9) felt compelled to help for a short period of time, yet after their interest waned, my intense urgency to make masks persisted. In comparison, mask making for me (author 2) stemmed from a desire for connectedness with my older cousin. My mom and I drove from my sister's house to visit with my aunt. My cousin had her sewing machine out, and she was filling special orders for making masks. I saw the supplies on the table, and she said, “Do you want to learn how to sew?” And I said, “Absolutely!” Her invitation was not only to learn to sew but also to help our community.

Crafting embodies a potential exigency for everyday activism, or craftivism, to help cope with mounting stressful conditions of the pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people felt compelled to learn how to and share knowledge about mask making. For example, the CDC showed a four-layer bandana method, demonstrated by Surgeon General, Dr. Jerome Adams (CDC, 2020). Yet sources such as the “Mask Effectiveness” statistics released by the New York Times cited research from Missouri University, Wake Forest Baptist Health and the University of Virginia which indicated that masks made of two layers of quilting fabric filtered out 70–79% of < 0.3 micron vs. a four-layer cotton bandana, which only filtered 20% (Enrich et al., 2020; Jennings, 2020). Comparatively, crafting masks with multiple cotton or even flannel layers provided safer, more health protective options.

Yet, craftivism involves turning what is historically known as a domestic craft into public community support. Craftivism can function as a “gateway” to civic expression and participation in that it can also connect with older generations (Literat and Markus, 2020), who learned domestic crafts to fulfill household maintenance. Makership, even in amateur form, can illustrate how “the creation of things by hand leads to a better understanding of democracy, because it reminds us that we have power” (Greer and Safyan, 2014, p. 8). Craftivism is specific to a group of people, traditionally women, who have experienced various forms of oppression. As Chansky (2010) articulated,

The needle is an appropriate material representation of women who are balancing both their anger over oppression and pride in their gender. The needle stabs as it creates, forcing thread or yarn into the act of creation. From a violent action comes the birth of a new whole. Women are channeling their rage, frustration, guilt, and other difficult emotions into a powerfully productive activity (p. 682).

Mask-making efforts could function as a form of feminist resistance in that sewing metaphorically embodies emotive process and production. As an emotive production, sewing channels manifest feelings into a functional craft, yet that functionality depends on layers of access.

As a “domestic” art, craftivism developed significance from its potential for accessibility. Sewing can resist what Audre Lorde identified as “master tools” concerning forms of resistance (Lorde, 1984, p. 2), and men's craft usually utilizes hard materials, such as wood, metal, or stone. However, an agency with any technology lies within its distribution and user access to historic knowledge, technological material, competence, comfort, and confidence (Blackmon, 2007, p. 160). Historic forms of sewing as craftivism range from the suffragettes sewing protest banners to activists sewing the AIDS memorial blanket (Gambardella, 2011; Price and Hawkins, 2018, p. 17–18), but those “historic” forms are inherently white historic forms. Considering the historical connection craftivism has to women's lives (Fry, 2014, p. 869; Close, 2018, p. 4) and the connection with third wave feminism (Chansky, 2010, p. 685–6), critical contemplation was required to understand how craftivist access may be constrained due to forms of racial privilege.

During an economic shift from traditional masculine capitalism, which occurs during crisis, alternative economic forms can resituate cultural privilege, or, as noted by Ahmed (2012), “power can be redone at the moment it is imagined as undone.” (p. 13). In a board gaming group of which I am a part, I (author 1) noted that a few of my friends of color said they didn't have a sewing machine and they had never learned to sew. Their responses made me stop and think about how a crisis can freeze communities in space and time when material access and knowledge was not within dispositional agency. If people did not have a sewing machine and knowledge of how to sew or craft a pattern, how might that influence their ability to feel an ability to respond by making masks?

Even when attempting to serve feminist ideals, when a new institutional dynamic developed to serve a population through mask making, many cultural infrastructures and networks of power still reinforced racial hierarchies and values. During the pandemic, physical exposure and risk continued, especially when considering the exposure of many BIPOC due to a probability of essential work positions. Research at the University of Utah Health (2020) found that more Black Americans worked in essential jobs with high exposure rates to SARS-CoV-2 meaning BIPOC risks of exposure were higher than white people as they attempted to retain an income to survive the pandemic. Research from the CDC and global data illustrated the escalated health disparities people of color faced concerning not only COVID contagion, but also severity of effects and heightened racism based in “biothreat” fears (Kim et al., 2023, p. 06; Watts, 2021, p. 10–11).

COVID exacerbated systemic and institutionalized racism and sexism as seen through reported fears of similar medical abuses such as Tuskegee (Zhou et al., 2022), disproportionate risk factors COVID-19 on communities of color (Fortuna et al., 2020), and increased in service expectations and isolation of women and mothers of color during the pandemic (Elhinnawy, 2022; Blell et al., 2023; Flores Sanchez and Kai, 2023; Melaku and Beeman, 2023).

I (author 2) too considered the impact of creating masks to mitigate the limitations many faced due to the limited supply of the coveted N95 masks. Unlike my co-author, I did not know how to sew...at least not well. Being of the age where home economics classes were still a thing, I learned how to sew many moons ago but had developed an unwarranted fear that I would stab myself with the needle or irreparably damage a project. Although intrigued by the possibility of creating with the sewing machine, my fears usually won out and prevented me from exploring this skill any further. However, in June of 2020, I put that fear aside and asked my cousin to teach me to sew so that I could join her in making masks to help out during the crisis. She happily obliged and engaged me in an intensive 2-h, sewing bootcamp. She taught me sewing basics in the context of making a mask. We didn't use a formal pattern or spend a lot of time measuring twice and cutting once. In fact, we used one of my favorite masks as a template to create the pattern. For the next 3 days, I helped my cousin design, cut fabric, and sew masks for people in our communities. It was so much fun! I felt pride in knowing that this new skill could help others, especially those who I loved and cared for the most. I enjoyed the mask making so much that I planned to continue once I returned home to Pennsylvania.

Many of my (author 1) Black, Indigenous, Mexican, and friends of color worked in high risk spaces thus placing them at greater exposure to SARS-CoV-2. I recall one close friend who identifies ethnically as Mexican and Black, who was required to go to work as a security supervisor at a major hospital. When I found out that she did not have access to a mask early in the pandemic, I was so afraid for her life, her family's lives. This woman, who was part of my wedding party, who I had spent every New Years' Eve with, and who was at the hospital the day our second kiddo was born, how could I help her?!? How could I support her and her family?

A family member of mine offered us N95s, which I quickly arranged to give to her. As a front line worker she had been told that the masks were only for the nurses and doctors. My stomach even now tenses up as I recall her and I sitting in cars near one another in a hospital parking lot, crying out of our fears that we or our families would not survive. I knew that I had privileged access to resources as well as the privilege that me and my family could stay home, could quarantine, and not fear the loss of our jobs or home or health. I also knew that I needed to do more.

As my co-author learned how to sew, by the end of spring I had already sewn many masks, solidified designs, and delivered them to friends and family. As summer began, I started making custom designs for staff at the pediatrician's office, their pediatrician, and our pediatrician's spouse. When our childrens' pediatrician saw the work that I was doing, she asked if I would help at her church. At that time, I declined. I had reached a tipping point in resources (materials, time, etc.). I was also concerned about having religious institutions distributing masks. As an agnostic, I feel suspect of benefactor type relationships tied to religious conversion. I didn't want masks to be used as religious capital.

In addition to the physical health protection benefits noted above, creating custom masks makes them stylized and personal rather than sterile and clinical, as material manifestations of connections and one's role in preserving cultural community within a public health crisis, or a support of mental health. Appreciation from neighbors and recognition by public community members represent the social capital that crafters earn by using their fiber voice to develop an alternate economy that supports communities facing a crisis. As noted by Castells (2012), “[w]hen we talk about the aftermath [of a crisis], it is not indicating that the crisis has ended. On the contrary, the crisis is unfolding and accelerating…but, at the same time, what is happening is that a new landscape of capitalism...is being created.” Castells was speaking of the economic crisis in 2012 but parallels exist for the coronavirus/SARS-2 crisis in which new economies emerged to respond to healthcare needs such as sustaining materials like food, toilet paper, and even masks. Because people were expected to reside indoors, mask-making efforts skyrocketed (Enrich et al., 2020; Jennings, 2020). Yet, as noted by Christine Harold in her book Things Worth Keeping, “[m]aker culture, in my observation, is not opposed to capitalism. Rather, it is tinkering under the hood of those engines that make capitalism run, demystifying their inner workings, and experimenting with the possibility of an alternative form of consumption and scale, one that works to make our technologies appropriate,” (Harold, 2020, p. 207). Mask-making efforts fell outside of what Hackney called “masculine capitalist culture” (Hackney, 2013, p. 175), instead becoming the hub of an alternative economic culture of craftivism in that many makers were white women completing the work in their homes. Across our communities, small businesses capitalized on local mask design to form the alternative economic culture being woven inside living rooms, and we could support our local community members for their mask making. Yet, alternative economic cultures require adaptability and sustainability found within social cultures.

2.2 Craftivism as networked access

In the case of my (author 1) mask making efforts, only through pre-established networks, especially on Facebook, did I access materials such as common designs, precut fabric, and elastic in late March. Both Facebook groups to which I belonged (Twin Cities Mask Makers—COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic **RESPONSE TEAM**, 2020; Twin Cities Mask Makers—COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic Volunteers, 2020) identified themselves as “private” pages for volunteers, meaning that only invited, networked, and accepted members could take part in the groups and have access to materials offered. I felt a sense of public, my contact and FOAF network, emerged when a Facebook contact shared with me a local fabric store offering mask making fabric packets. Getting resources seemed easy to me—I was privileged to have knowledge, networks, time, and local access to materials.

Alternative economic cultures may seemingly flourish through a “sharing economy,” yet developments are contingent on one's network. In the case of coronavirus/SARS-2 crisis mask-making resources, “digital intermediation platforms” (Karatzogianni and Matthews, 2020, p. 96) became a lifeline to a supportive public. Harold noted that “[m]aker culture is about doing it yourself or doing it with others.” In its loftiest rhetorical moments, it highlights values of openness, collaboration, and flexibility; it champions human-scale technology. It is animated by a karma system or reputation economy, in which makers are more interested in making a contribution than making a profit. That said, “profits are being made by maker businesses” (206). Yet, neoliberal vision asserts that, if you “get enough people in your network, everything is going to be okay” (Karatzogianni and Matthews, 2020, p. 105) which illustrates a dependence on the affinity structures of social media. We cannot forget that openness, collaboration, and flexibility all rely on people's willingness to connect, commune, and be vulnerable with one another. White network boundaries and “privilege filters” (Anderson, 2021, p. 17) continue cultural inequities through claims of race neutrality, perpetuating the cycle of oppression. Both makers and wearers of health preserving technologies, such as masks, are infrastructurally discriminated against, containing health responsiveness.

Public commons exist within an affinity structure, or a friend and “like” based network, afforded by particular technologies; yet, digital networks are as subject to racially homogenous structuring as offline groups. Examples such as crafting in a public library, which functioned as a multicultural site for public community formation and deliberation (Robinson, 2020), seemed unlikely during a pandemic. How could I (author 1) help teach or learn from those friends of mine who do not have machines or knowledge or new tech resources like Zoom or Facetime?

Empowered by my (author 2) new sewing skill in July 2020, I took to social media quickly to seek out and join several online groups devoted to crafters. In these groups people readily shared patterns and designs for cheekily messaged masks adorned with phrases such as “Stand Back! You're TOO Close!” or “Sorry for what I said while I was in quarantine!” I assumed this online group was a safe space where all ideas were welcome as long as they weren't racist, misogynistic, or otherwise discriminatory. Many brought their latest craft ideas to the group for feedback, looking for moral support and encouragement; a craft swap meet of sorts, a pattern for an image, an image for a vendor, etc. Although I started out in two craft groups that were predominantly white women, my sister (a fellow crafter) recommended that I join a few “Black Girl” craft groups as they provided a more representative embodiment of diverse content than in the white groups who sometimes questioned or even censored that kind of content.

By curtailing what people put on masks, an administrative white frame disciplined participants' individual and vernacular (Ono and Sloop, 1995) community agency. People with knowledge on how to guide or mentor people may choose to limit what they offer people who do appear “different” or not in line with one's politics or seeking to forward one's political or professional agenda. Community vernacular contains survival, as seen with mask-making groups and activism such as Black Lives Matter. The support for mask making through white women social media networks who prompted the idea of “being inclusive” and then ostracizing pro-Black content as “political” illustrated a social containment. In activist and other settings, continued tone policing of BIPOC perspectives ensures white comfort and privilege (Lorde, 2007; Calafell, 2015; Nuru and Arendt, 2019; Winderman, 2019). Whiteness, as a perspective frameset or default, became a mitigating factor to network inclusion within a digitally mediated social group.

Upon reflecting on our access to materials and networks, crafting during a pandemic seemed to be bound up in individual, white knowledge and access based on historic material privilege. Craft knowledge of sewing is historically situated with ownership of a machine. Dispositional agency is dependent on access or whether or not Black and Brown people have the knowledge and are willing and able to seek the knowledge within their social “pod” networks. Similar to how academic work functions within academic spaces, what is epistemologically held as “knowledge” continues to be contained to a small group of people within privileged networks. A pattern functions as an artifact developed from a particular gaze and knowledge. Similar to the diagrams of slave merchant ships as noted by assistant professor of African and African Diaspora Studies (Browne, 2015), privileging “white gazes and vantage points” embodies power through an omnipotent observer quality (p. 49); where one's vantage point frames the record yet one is not recorded as the recorder. A pattern functions to show, yet not show oneself; “to represent while escaping representation,” (Haraway, 1988, p. 581) yet the “gaze” on an implied face model (fine framed-white, female) becomes an assumed figure to preserve. Knowledge of sewing and machine ownership provided an agency to produce and revise masks in response to the crisis. Yet, without material access, one would have to focus on fostering a disposition to gain knowledge and sewing machine access.

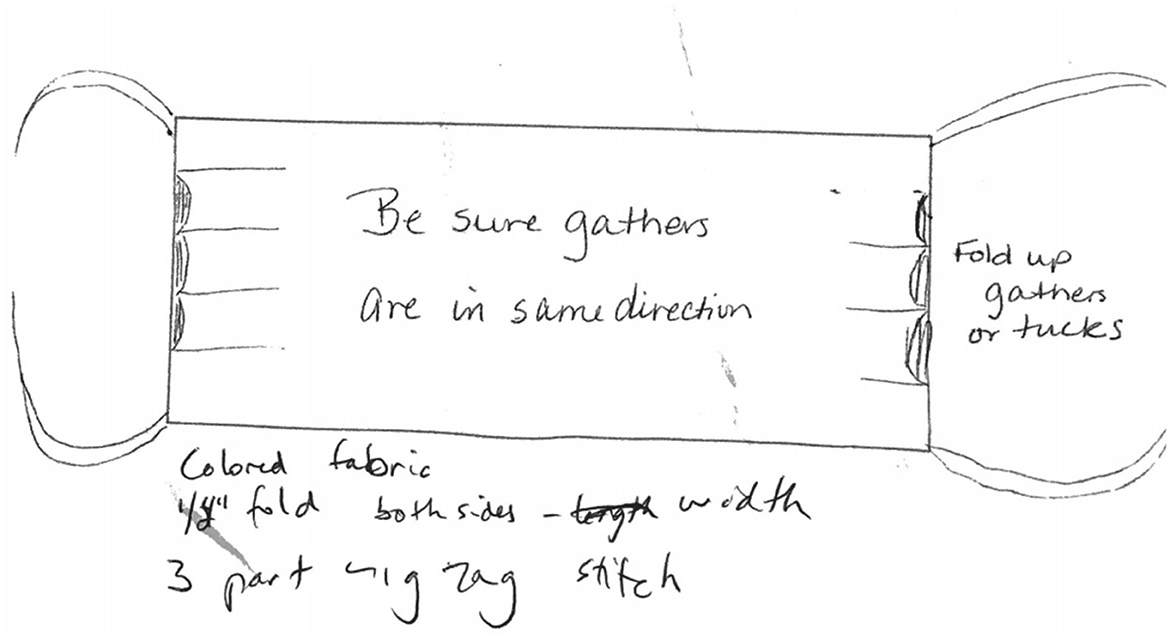

In an ocean of resources built for me as a white woman who sewed, I (author 1) had agency to understand mask effectiveness and mask design and construction in late March. I could sew almost alone because I had the skill set and the patterns seemed to be made using a white model and frame. Unlike author 2, I had found two different patterns, the deaconess and the accordion styles. My sister and I looked at designs that left a filter pocket—from shop towels to the plastic reusable bags—and even found mask making Facebook-based community groups in the Twin Cities (named the Twin cities mask makers and the coronavirus response team and COVID-19 Coronavirus pandemic volunteers) who were providing free, pre-cut cloth. My sister dropped off my first mask sewing kit complete with an accordion style pattern (See Figure 1), pre-cut adult aqua and purple dots on a white background fabric and child-sized prancing unicorns, reclining mermaids, and zooming airplanes fabric, and elastic for around the ears. The materials felt soft between my fingers, yet also sturdy. I thought hopefully kids will feel comfortable in the shape and like these patterns enough to wear them. I tried making one and found that I wanted a live tutorial.

Figure 1. Cities Mask Makers—COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic **RESPONSE TEAM**. The handwritten additions on the bottom of the page under the handwritten image are the pattern modifications by author one during mask construction.

The Rebel Lens (2020) on Facebook offered a video, what Harold called a “process narrative” (171), so I adapted the pattern (¼” fold to liner and outside fabric on the width of the fabric and a 3-part zig zag stitch) and sewed in a liner. I stopped and restarted the video until I understood and could replicate each step. As I created masks and tried them out on myself and family members, I started to wonder if the masks I was making would fit everyone. And how could I have people try them on without increasing the possibility of anyone getting COVID? I quickly enlarged a pattern and adapted the pattern again to modify the elastic ear loops by cutting them in half and sewing modified shoelaces around the head. As my friends tried them on, I noted that many masks did not fit the faces of my Black and Brown friends of color. When a friend of color told me that she wanted to help but could not sew, I first reassured her that we all help in the ways we can and slowly realized that many of my BIPOC friends lacked the privileged access and knowledge of sewing and the time to adapt a pattern.

The use of a pattern functions as a representation, a shadow on the wall of the cave (Plato, 2017), a simulacra (Baudrillard, 1994, p. 20), a rhetoric or reduction that offers agency in praxis, in the case of craft, requires contextual knowledge to move into action. One must not only understand the pattern to use it but also recognize that a pattern is decontextualized from the “real” or “model for whom the pattern was designed.” Pattern is a representation of a real, yet the process is practicing a technique or learning the skill set. In the case of many patterns found online, the model was based on an episteme of a white woman's face and the pattern, as a technology, erases race as it represents a contained pathway to agency. As noted by Benjamin (2019), “[t]he animating force of the New Jim Code is that tech designers encode judgments into technical systems but claim that racist results of their designs are entirely exterior to the encoding process” (p. 11–12). A pattern decontextualizes a model as context for the design, making racism appear race neutral, both invisible and ubiquitous, due to a technological mediator, the pattern.

Further multicultural information sharing relied on pre-existing multicultural social networks; otherwise, white people just supported the health and capital of more white people. Not only the pattern itself but also the process of finding a pattern and even materials can embody a privileging agency. I (author 1) was struck by the social media network on Facebook that allowed me to find the advertisement for the free fabric packet from a local fiber shop. Local networks mattered in my ability to craft masks to protect and preserve people's health. Yet, Farinosi and Fortunati noted how craftivism, such as “urban knitting,” was characterized by “the use of digital media and social platforms for information sharing and protest coordination” (Farinosi and Fortunati, 2018, p. 148). Later when I (author 1) returned to the link to The Rebel Lens (2020) group on Facebook, I realized that without my prior network and knowledge, I wouldn't have found the video post to begin with or even realized that I needed a new mask pattern. Although the video featured a man of color, each group on Facebook was a white owned and managed space, which earned white people social and/or monetary capital. As noted by Associate Professor of Gender Studies and African American Studies Safiya Umoja Noble (2018), the distribution of Black and Brown work online by white organizers illustrates a type of capital within a “controlled, neo-liberal communication sphere” (p. 92), where social capital shared by BIPOC can turn into fiscal capital for white women. Similar to how Google search algorithms gain profit from the hypervisibility of searches for Black girls (Noble, 2018), the Rebel Lens brand takes credit, an ethos, as it presents the demonstration of how to make a mask. The crafter in The Rebel Lens video, a man of color from Minneapolis, sits in a sterile hospital-like environment making masks for their community. Yet, The Rebel Lens moderators decided how that video content was shared and hosted the video on their space, controlling the content and gaining the ethos/credibility of the knowledge of the man of color who demonstrated the sewing knowledge.

Years after the start of the pandemic, I (author 2), in some ways, am still seeking the right mask. I spent weeks searching for masks. I searched online for multipacks, so that I would have enough to get me through each week. At first, I thought simply having 7 masks would be sufficient, but panic set in and I searched for replacements for my replacements. I became quite obsessive about making sure that I had options, both for fashion and function. Some experiences were fruitful, like the masks I purchased from Target, while others were not. I recall one disposable mask order arriving in the mail and when I pulled out the first mask the ear loop was already detached. The ear loop on a second mask snapped as I stretched it to fit my face. I remember feeling quite at the poorly designed masks. I was angry that I'd spent money on a product that was malfunctioning. It was an inconvenience for sure, but I had a moment where I needed to check my own privilege. Unlike some, I had the resources to buy or make more masks if they didn't work. But what about those who did not have this same level of access to resources or skills to make or buy new masks?

My handmade masks, which are in various forms of completion, are currently tucked away in piles in a storage container. Others that were completed were given away or personally worn. The fits vary and with that, so does the level of comfort that I experience while wearing them. I purchased masks for special events or outings, including working out. Unfortunately, my slim-fit, aerodynamic mask kept falling off mid-workout causing concern about whether I had inadvertently exposed myself to COVID or God-forbid, someone else to COVID. I'd read the packaging to ensure that the chosen mask would fit my needs, but it still felt as if this fitness mask wasn't meant for me.

2.3 Craftivism as privileged time and fit

Over the first few weeks of making masks, I (author 1) dove into researching designs, while some of my Black, Indigenous, and friends of color, especially those who worked in “essential” positions, just tried to survive (I recall stories of stripping outside of their homes after work to jump into showers every day and of the horrors of watching people die from COVID). That time I “had” for making masks was afforded by not working two jobs or working overtime to keep my family afloat. I needed to test masks on people, a range of people, without contaminating the masks. Fortunately, I had four different face sizes in our households. When my partner—is a 6′1” white cis man with an athletic build—tried on the adult size, which mostly, but not completely fit my partner's face. By my fifth mask attempt, I had one that fit my partner's face, but only if I had sewn the accordion style mask with a certain pleat size. He commented that his large lips and broad cheeks might require more fabric, but I also saw how the sewing of the accordion folds influenced how the masks fit. Our youngest child reported that the ear straps were uncomfortable. I took care to redesign the masks by attaching the existing ear straps to shoelaces I had around the house. All this adaptation required materials, knowledge, time, and a network through which I could access all of it. The language of craft was contained by the privilege of knowledge of the craft. I not only had time to research, but also to wear and revise mask designs that I worked on. I would be remiss to note that one friend, who identifies as a Black woman, did make masks in the summer (July-August of 2020). She knew how to sew and owned a sewing machine so she adapted mask patterns to “regular” and “large” sizes (See Figure 2) and even made masks for my partner and brother (who were struggling to find masks that fit exceptionally well).

Figure 2. Enlarged deaconess mask pattern. This is the deaconess-style basic mask pattern enlarged by a friend (author 1) of color to ensure it fits faces of people of color. The measurement on the right side was added to provide consistency in sizing.

Standardized medical mask designs would fit only certain groups of people who have biologically adapted to colder, northern regions when compared with people from warmer, southern regions.3 Medical equipment research has documented racial differences in fit of respiratory, protective equipment (Zhuang et al., 2010, p. 391) yet did not show mask design updates in mask templates. Mask designs for an accordion style mask (Figure 1) are based on surgical mask design, the same masks in the aforementioned study.

I (author 2) did have one mask that I really loved; it happened to be the very first handmade mask that I purchased from a designer seamstress who attended my childhood church. When the lockdown hit, she posted on social media that her business was shifting gears to assist with the mask shortage and that they'd be selling masks. I purchased a mask not only for myself but also a few extras to protect my immediate family. When the package arrived, I got first dibs. I chose a two-layer design made with alternating African print and solid fabric. It was the perfect balance of style and function. After what seems like infinite washes and wearings, it remains my favorite. In fact, I used this mask as a template for the very first mask I sewed. At my cousin's direction, I traced my mask on a piece of paper, cut out the design, and used that design to cut out fabric pieces to make the masks. The first mask was comically huge because I overestimated my seam allowance. Instead of looking for other templates, I painstakingly trimmed my pattern centimeters at a time until I reached the ideal size. My proudest moment was right after I finished the final stitch on my first mask. I chose a gray fatigue print for the outside and a solid glossy black for the inside. As I monogrammed the mask with his initials, I anticipated seeing him wear my creation, knowing that while wearing it, he'd be protecting himself and others. I was crushed when he tried it on and it didn't fit. I fixed it by purchasing adjustable toggles, eventually seeing my work come to fruition as he proudly donned a properly fitting mask.

I have tried and now own nearly 30 different masks. There are some that fit well and others that fall off my nose, pop off my ears, or drop from my face completely. I can make them fit well enough; making do with what I have–making the best out of the situation. While I found success in my first mask, members of my family weren't as lucky. Both my mother and nephew struggle with mask fit. My nephew is a 6′1, heavier build, bearded, Black cis man and most masks cover only a sliver of his face, leaving key areas exposed. When choosing a mask, he often must decide which vulnerable orifice he'd like to protect-his mouth, or his nose. He often chooses to cover his mouth, leaving his nose exposed and vulnerable to potentially inhaling airborne contagion. Unsurprisingly, my nephew complained that the mask was too small, but he refused my offer to make him a larger one. Instead, he often opted to forego wearing a mask completely. I immediately felt a sense of concern and worry for his safety. Would he continue to undergo the labor of trying to find the right mask or give up due to frustration? My mom had the opposite problem. She is a petite, small-framed cis woman for whom most masks are too big. She is also high-risk due to chronic health issues that have plagued her for nearly two decades; the need to protect her seems even more crucial than others in my family. I have taken it upon myself to assist her in finding a good fit. We've found that traditional masks fall off her face, exposing her nose. She experiences gaps along her cheeks in the homemade masks, resulting in potential exposure of both her nose and her mouth. I purchased a neck gaiter with ear loops in hopes that this would provide better protection but have found that the ear loops fall off providing the same result. The search has cost me hundreds of dollars, wasted time, and endless frustration as I found again and again that all masks are not created equal, which is to say, not created with diverse face shapes in mind. To date, the best option that I've found for my mom is not a mask at all but a reusable plastic face shield.

Discrepancies of face shape and the problematic fit of respiratory gear during the pandemic offered means for actionable change when reviewing initial research. For example, the accordion mask design shared online between many organizations, including the local fabric store mentioned above (see Figure 1), would not fit most Black adults when compared to many white adults, mainly white women. As noted by Ahmed (2012), changes in policy (e.g., making masks locally) without changes in procedure (e.g., distributing larger patterns) continue to privilege specific individuals, namely white people (p. 11). Mass distributed mask styles for amateur mask development illustrated the privileging of white people's health over Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, Mexican, and other racially underrepresented groups' health concerning the prevention of COVID. Furthermore, when larger masks came on the market via brands like Under Armor, they became one of the most expensive brands on the market (Rolling Stone Editors, 2021), continuing the inequity of fiscal access to BIPOC who biologically have larger face structures. Yet, dispositional agencies prompted people adapted “large” masks to wear and sell. Further as shown.

In fact, my (author 1) friend's pattern worked so well that she started her own Etsy store in August of 2020. She even employed kids of color in her network to help with per-mask compensation. That story had a happy ending, but it was after months of struggle to adapt her pattern while also working full time. Additionally, she also charged significantly less for her well-made mask than online retailers, $2–$5 less per mask. As the World Health Organization noted the amount of reported cases in the US from 1 April 2020 to 1 August 2020 increased from 204,160 to 4,675,668 (Elflein, 2022), I found myself wondering how many people contracted COVID because of not having masks that would fit as they carried out their activities required for their survival.

Physical risks and mask-making defaults illustrate white supremacy of institutions, procedures, and medical instrument design and development. Mask patterns posted on hospital websites such as Deaconess Hospital (2021) continued perpetuating white women as default sizing, while limited group discussion on sizing alternatives relied on one's experience in sewing to adjust design sizing. White supremacy operates at structural levels such that, unless you have expertise in the craft and anti-racist intentions, the way in which white supremacy functions just becomes part of a pattern of practice. Since research detailed over 10 years ago (Zhuang et al., 2010) that a discrepancy existed between surgical mask fit on people of different races, what actionable step is being missed in implementing policy changes in mask design? Further, how would the cost of purchasing a larger mask further discriminate against BIPOC? Singularly oppressed individuals, in contrast to those at the intersections of oppression (Crenshaw, 1989, p. 140), illustrate Chávez's concern that we need to focus on the most vulnerable population to understand how subtly oppression functions within our communities (Chávez, 2013, p. 30).

2.4 Craftivism as privileged physical risk

As the pandemic continued, the epidemic of racial injustice and demonstrations of civil unrest happened across our communities in the summer of 2020. June was marked by worldwide protests; some referred to this period as a pandemic within a pandemic. BLM protestors were encouraged by organizers to wear masks, and many wore masks emblazoned with “Black Lives Matter” or “I Can't Breathe.” Some online crafting circles reacted with backlash.

In my (author 2) crafting group, some members expressed their discomfort with seeing people wearing the BLM masks while others responded with outrage and racist commentary. Not only was privilege evidenced in the creation of masks due to material access and resources for their design, in some cases, the specific creative content was problematized when it did not feed back into the narrative of the privileged. What should have been a space open to creative, peaceful strategies for protest turned into an angry and racially charged space. I was left thinking that even in craft spaces, there is a privileging of certain voices, perspectives, and experiences, thus limiting opportunities for diverse expression.

While getting into my (author 1) mask modification, my sister mentioned a shortage of elastic for the masks. I wanted to make sure I had enough fabric and elastic, so when I read on Facebook about a local sewing shop giving away free fabric kits, I packed my oldest kiddo in the car and found myself a mile away from our rental home. What I remember from that day is the line of white women outside a closed shop on a Tuesday morning at 10 am standing every 6 feet down the sidewalk.

When I finally got into the store, the store owners announced that they ran out of packets the day before but offered that we could purchase what cloth they had left. It was clear that the tartan fabric was old inventory that had been passed over year after year. I walked out sans fabric and angry–angry that it felt opportunistic of the store owners to not communicate they were out of kids and try to push old stock. Even though that store ran out of their “kits” quickly, it received extensive press on their “free kits” as free promotion of their white-owned business via radio, newspaper, and social media, which prompted access of fabric to more white customers as well as sustained their business during a pandemic that ended many others.

Due to how identities proceed BIPOC, the risk of bodily exposure every time people leave their homes or their communities places BIPOC at increased risk in pandemic crisis situations. In addition to standing in line at stores as physical exposure, as expectation and requirements of mask wearing continued, articles surfaced detailing concerns from Black, Indigenous, People of Color about the safety of BIPOC wearing masks—this time in the context of the racial profiling that began to surface when white people saw POC in homemade masks (McLaughlin, 2020; Robertson, 2020; Thomas, 2020). In an interview for the Washington Post, one middle-aged Black man explained, “Appearances matter…I have pink, lime green, Carolina blue so I don't look menacing. I want to take a lot of that stigma and risk out as best I can” (Jan, 2020). Racism was intensified and committed against Asian Americans who were erroneously viewed as a source of the coronavirus. This racism has continued to fester as evidenced by the increase in violent and murderous acts committed against AAPIs. The problem of exposure is evident in Black and Brown communities as well, especially for men. Michael Jeffries, a Sociologist from Wellesley College, remarked that,

Black folks can't even wear hooded sweatshirts without being accused of being criminals...To issue guidance like this without any historical awareness—especially given recent and traumatic history—it's going to be hard for people to follow that advice, considering the consequences, which are literally deadly (Jan, 2020).

The criminalization of Black men creates an environment where mask wearing by Black and Brown men can be interpreted as a heightened risk state. As clarified by Nurse and Keeling (2023),

For many Black men during the pandemic, masking in the present was conditioned by at least two swirling discursive histories: a neoliberal health discourse of personal responsibility and a racist discourse attacking the Black Collective Corporeal Condition. A neoliberal public health solution to COVID was to mask up, which created the potential of racist violence against Black men, whose presumed criminality and dangerousness was heightened by wearing a mask (p. 192).

Black folks face a catch-22 that white people do not. By not following historical guidance, Black people expose themselves and others to potentially fatal diseases and step into the Black criminal stereotype assigned to them. Wearing masks may mitigate contagion and infection, but it attracts the same level of prejudice and persecution, if not more.

I (author 1) recall when a mother who would identify as white at my children's school pulled me aside 1 day to talk about how one of our administrators, a person of color, struggled to keep a mask kept falling off their nose. I immediately asked her, had she bought them a larger mask-I was met with silence. I ordered two masks for them from a BIPOC making masks and wrote a card to them noting that one of the other mothers had said something to me about their mask falling. All I could think about was how closely they were being observed and how unethical judgments occur when access to equitable mask protection is not available.

As we have seen during the protests of the George Floyd murder, concerns spread about how BLM protesters would share COVID-19, yet research found, “Since approximately 40% of counties where a BLM protest occurred saw a smaller increase in COVID cases at Week 3 than their comparison counties, it is clear the BLM protest cannot explain a rise in COVID rates” (Dave et al., 2020; Neyman, 2021; Neyman and Dalsey, 2021). Increased fears of COVID spread may have functioned as a form of apologia for people who already did not understand the gravity of the protest. Yet, the more severe concern came in the form of violence against Black and Asian Americans as well as BIPOC people continuing to police themselves from engaging in their civic rights (Ruiz et al., 2020).

Now in 2023, the policing, panoptic enforcement as well as what we see as self-enforced “cultural paranoia,” where we police ourselves in fear of being seen (through symbolic representations of a mask) and judged as different, continues, as we put ourselves into health precarity to preserve someone else's comfort.

In the last year, I (author 1) found out that I have breast cancer. Why is my diagnosis significant? A colleague and friend who had breast cancer and had been supporting me through the treatment process sent me an article released in the journal Frontiers in Oncology, which highlighted a relationship between COVID and a mutation of breast cancer cells (Nguyen et al., 2022). Furthermore, after my radiology treatments, my radiologist and oncologist both noted that my lungs will be compromised and I should avoid getting sick by masking up again.

I recall a time when, at the tail end of my immunotherapy, a scouting group of which I am a co-treasurer was hosting their last event—the derby car race. The morning of the event in the group leader text chain one leader admitted that he had been recently diagnosed with COVID and asked if it was okay if he wore a mask and attended the event. I remember taking a beat and writing back to everyone that he could choose to take care of himself and stay home. I know that it was selfish of me-we both have kids in the group, but I felt like I had been through so much, losing my hair, throwing up, missing so many events, the least someone could do is offer those of us who are immunocompromised space by staying home when sick! And what about all the other families who are not a part of the leadership text chain? They would unwittingly be at the mercy of his decision.

My partner and I talked about me masking up—I decided not to because how did that make any sense? Kids touch everything—they spread so many germs that unless our kids masked, would it even matter? I decided not to and next to our car pulled up the parent—maskless. I found myself moving into full evasion mode—limit my eye contact and create distance between us. When he arrived at the pavilion, he did mask up. The outside event made it easier to distance until it was race time—that parent chose to sit at the computer, in the thick of things. Their mask was sometimes on their face and down at other times, even as other adults and children crawled all around them and they yelled to people if the computer set up was ready to record the times and places. I remember not being in the pavilion, socially isolating myself, trying to communicate with my partner to keep our kids who just wanted to be in the thick of things, distanced from this parent who was managing the computer. Our kids not only wanted to help but also wanted to see how the digital display worked. I sat in the shade of a tree hoping that no one would get COVID. I felt relief the minute we could leave the event. I know that I should mask up—I know it intellectually—but I feel this fear of social shaming, or being seen as a victim or perpetrator, of marking myself as different and not sharing some of the most expressive, socio-emotional parts of my face. More importantly, research on COVID spread indicated that masking is more effective when the person with COVID masks as compared to a person who is not sick (Wang et al., 2021). Further as a woman, I do not want to make myself a target and I do not want to feel vulnerable because I am then at the mercy of others' compassion. I want to keep my difference hidden, so my difference doesn't proceed and supersede the perception of my humanity.

Even recently, I (author 2) have experienced some policing and precarity around masking. I work in a large hospital setting where wearing a mask, especially at the height of the pandemic, was not questioned. I'd become accustomed to masking and even found a level of safety behind the mask. As COVID numbers began to decline, our masking requirements at the hospital became more relaxed. Instead of a mandate, we gradually moved to strong recommendations and finally to masks only being required in direct patient-facing and treatment areas. It took some time for me to feel completely comfortable with not masking, especially in enclosed spaces such as an elevator. You may still catch me from time to time masking up in an elevator. On one such day, I entered an empty elevator headed to my department to start my day. An older white man, assumed to be a patient because he did not have a badge, entered shortly after followed by another employee who was not masked. The older man turns to me and states, “you know we do not need to wear those any more.” I say nothing but simply shake my head in the affirmative so as not to engage further as masking in Texas was highly politicized and I didn't want any trouble at the start of my workday. While I could have interpreted the man's statement as an encroachment and in some ways, I do see it as a sort of policing of my experience as a human being; I chose to quietly acknowledge his statement without engaging further.

Just a few weeks back, once again on the elevator, I encountered an older Black couple. This time I was not masked and even still, questions or comments about masking arose. Unlike the previous gentleman, this couple was concerned and confused about compliance. The Black man from the couple shared that he “did not know what the expectation is” when it came to masks. He wasn't sure if he needed to mask up or not but the look of concern showed that he wanted to make sure that he was doing the right thing. I explained that the masking requirements were lifted but that it was a personal choice if they felt more comfortable wearing the masks. They were thankful, thanked me for the information, and went about their day.

Here, we are at the end of August 2023, with COVID numbers creeping up again and two people from my research team recently testing positive for COVID, and I have started to mask up again. Despite the news and reports of increasing numbers, which in my head, validate my personal decision, I am still grappling with conversations and judgment from others about my choice to wear a mask in public spaces. In my most recent encounter, I was walking down a hall when I was greeted by another employee. We have pleasant exchanges when we see each other so I thought nothing of their smiling greeting, “Good Morning Dr. X!” My smile, hidden by my mask, was bright and full of teeth as we approached, walking toward each other in the hall. I was happy to see them until they began to chuckle in an almost mocking manner. I furrowed my brow out of confusion as they gestured to my mask and said, “Paranoia?” and now audibly laughed as we walked past each other. I shook my head and quickly, yet aggravatedly responded, “No, not paranoia…Reality!” Here, yet again, my choice to mask was questioned and essentially made fun of due to another's assessment of my need to protect myself.

In the first encounter, I felt angry…I felt policed. I felt that if I had engaged the man that it would have turned into a big situation so I was silent…in the face of potential conflict over a choice I'd made to preserve my health, I opted for silence…I felt silenced. Even though I was confident in my decision to wear my mask and nothing he, nor anyone for that matter, could have said would have made me unmask, I still felt a bit angry that he felt it was his place to tell me what I was allowed to do as if he was some great liberator who had the authority to release me from the shackles of this mask. Reflecting on it now still burns me up a bit. I juxtapose that with the experience with the Black couple where they almost passively inquired about what the expectations were for proper behavior in this space. I reflected on what I saw in the second encounter as self-policing that undeniably felt other-serving and self-depriving. This couple was basing their decisions on what other people deemed as the right thing to do. In this third and most recent encounter, I felt empowered to immediately stand up for myself and my choice. My words were few but an immediate response to yet another trying to shame me as paranoid for wearing a mask.

It is hard to live our lives in a perception, even when accurate, of precarity. Yet, in these situations we realize how much we depend on others, men or even white women, to “take care” of us, to fight with us for our survival. We are reminded of historian/activist/scholar Reagon (2000) who wrote, “The ‘our' must include everybody you have to include in order for you to survive…That's why we have to have coalitions. Cause I ain't gonna let you live unless you let me live.” (p. 365). Yet, we wonder, what do we lose as well as gain in giving up or sharing our agency? How do we preserve both our physical and mental health and the health of our community through that sharing? If we cannot convince others to adjust to preserve our and other community members' health, how must our relationships change, what “compassionate boundaries” must we set to ensure we live? We realize that, although we have worked to gain an educational privilege where we can access, understand, learn, and know how to process information, due to our oppressed existence (physical, racial, gendered, financial, neurological, etc.), we do not have the safety net, bumpers, or cushion (i.e., nest egg or family support) if we or our community and family members' contract COVID. We and our community members face serious consequences if we contract COVID, which could vary from job consequences to death.

3 Conclusion

Through writing this article, we see how power sharing and negotiating privilege and oppression require compassion and a preservation of both monologic and dialogic voice to transform research practices and help us become more reflective in our everyday lives and assumptions, especially when faced with health crises. Craftivism in the form of mask-making responsiveness during the 2020 coronavirus/SARS-2 crisis reinscribed white privilege and power through white women rather than white masculine capitalism. A critical, autoethnographic approach revealed how white supremacy is privileged by historic materiality and knowledge (epistêmê), time to create and revise, networked access, and mitigation of risks. Through our research and praxis of mask making, we realized how white women demonstrated an immediacy of responsiveness to other white women and children through an agency of care, yet a delay in response existed for people who have been historically oppressed. Privileged access to materials (money, technology, homes, etc.) and knowledge (epistêmê) of sewing influenced BIPOC's ability to make masks (technê), our theory and praxis. Families pass down materials, such as sewing machines, furniture, and knowledge of a particular craft, a technê, which is subject to context and culture. In addition to the materials, technology, and knowledge, white women have the privilege of time and fit concerning mask designs to make and adapt, ensuring the safety and security of their cultural community members. More white women have the privilege of time and flexibility to modify mask designs for proper fit, ensuring the safety and security of their community members. Social media networks ensure breaking information on design adjustments or even “free” opportunities support their work as well as the organizations and businesses led by more white people. Further work is needed to transform a responsive ethic of care, even when it stems from a feminist perspective, can reinstate white privilege unless anti-racism guides production. Last, after masks were completed, some BIPOC communities feared and were less comfortable wearing homemade masks due to racially motivated discriminatory criminalization while wearing masks, a fear not experienced by most white people.

The privilege of accessing medical equipment is a form of white supremacy that is multi-layered and needs to be addressed to ensure equal, equitable, and ethical access to healthcare. More critical contemplation of patterns, processes, and practices as technological designs is needed as designers decontextualize racism through the use of seemingly “race neutral” technologies. The extent of continued discrepancies to agencies for healthcare access will be illustrated through impacts (deaths, healthcare costs, mental healthcare impacts, infection rates, etc.) of COVID statistically detailed in the years to come, not only in the U.S., but within vulnerable populations worldwide. In particular, the long-term effects of mental stress experienced by Black/African Americans due to having “both the highest levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the highest prevalence of fearing infection to a great extent” (Willis et al., 2021) should be researched further (Johnson et al., 2021). Furthermore, research on the change in procedures within the corporate medical industry detailing medical equipment development discrimination may help us understand how research is actionable and accountable steps toward racial equity. Recognizing differences in body make up is important when it comes to equitable design. Even reflecting on the methods and actions we researched to protect ourselves, only one of us (author 2) put those health precautions into action by constructing a makeshift mask (scarf) to preserve her health, which speaks to the discrepancy between a perception of risk and privilege of safety experienced by both scholars. Looking at how organizations reconfigure in 2021–2022 may offer insight into who will continue to benefit organizationally from any COVID-19 pandemic carryovers. Further technological developments are not value neutral. Benjamin (2019) noted that “[m]any tech enthusiasts wax poetic about a posthuman world and, indeed, the expansion of big data analytics, predictive algorithms, an AI, animate digital dreams of human bias and racism. But posthumanist visions assume that we have all had a chance to be human” (p. 32). In not being considered as a default model for a pattern, our humanity continues to be in question in that we are not included in a default conception of a body through our cultural, public, and vernacular communities. Until we recentralize intersections of racial and gender equity into our technological infrastructures, we will continue to perpetuate racial oppression, wittingly or unwittingly, within our communities through seemingly “race neutral” technologies. Anti-discriminatory policy needs to be mandated on the medical product development industry, mediated systems, and even our handmade designs for equitable changes to occur.

Additionally, regrettably even feminist responsiveness can reinstate white privilege. Without recentering intersectionality within our decision-making processes and procedures, we rely on historically white defaults. White defaults do not consider the white frameset that designed the intent behind, implementation of, and differing cultural interpretations of those decisions based on the varying impacts of those decision. Considering white nationalist movement, Tea Party, and the Republican party rhetoric of “American exceptionalism” (Anderson, 2021; p. 84, 127, 139, 145, 163), as manifest during COVID, the ideology “has been deadly—especially for historically resource-deprived communities within the United States” (Rowland et al., 2023; p. x). Without dialoguing with people unlike ourselves, our decisions are not equitable. Furthermore, intersectional perspectives offer insight into multidimensional criteria and impacts from “those with firsthand experience of the vulnerability about which they write” (Chávez, 2013; p. 30) and/or live, providing a larger net of who we reach as we implement our decisions. When we considered our autoethnographic approach, we recognized that some disciplines may not see our work as credible; yet, without our accomplice relationship, how can we make changes in our discipline and others? Without holding space for our dialogue which preserves both voices, can we truly understand our rhetorical situation and how technê can be culturally affording and constraining? Further autoethnographies, especially dialogic ones, illustrate comparative discrepancies when it comes to healthcare equity. By producing open source, narrative-based work, we see possibilities to open academic work, beyond field limiting jargon and form, to intellectual communities where people see options and possibilities to support themselves and their communities as well as reconsider institutional and organizational decision-making and communication. As we reorient ourselves toward anti-racist process and practices, we need to critically engage the impacts of COVID-19 based on early efforts within communities to assess how we might remake a more equitable infrastructure for sustaining diverse communities in future rather than recrafting white supremacy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for participation in the research and for the publication of potentially identifying information.

Author contributions

WA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. LD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes